How Analysis Goes Wrong: The Week in Awful Analysis – Week #3

How Analysis goes wrong is a new weekly series focused on evaluating common forms of business analysis. All evaluation of the analysis is done with one goal in mind: Does the analysis present a solid case why spending resources in the manner recommended will generate additional revenue than any other action the company could take with the same resources. The goal here is not to knock down analytics, it is help highlight those that are unknowingly damaging the credibility of the rational use of data. What you don’t do is often more important then what you do choose to do. All names and figures have been altered where appropriate to mask the “guilt”.

On this version of This Week in Awful Analysis, I wanted to start diving into the many false conclusions that people draw from the results of tests. There are problems from things like confidence, correlation, bias, and all sorts of drivers, but the most fundamental one is a failure to properly frame the result itself.

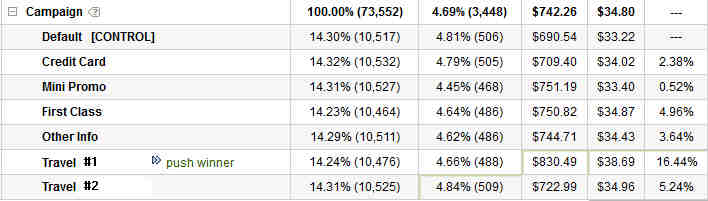

I want to walk you through a standard test experience. In this case, we are running a simple inclusions/exclusion test, where we see what the impact is of removing a certain item from the page. In this scenario, we ran our test, have gotten 1 week of consistent data (about 16 days total), have enough differentiation and enough data, so we are ready to call our test:

In this scenario we see we have a winner, and so we report this winner to our org, suggest we remove the section, and move on…

Except that is the only part of the story we allowed ourselves to look at, due to a failure to think about and set-up the test in a way to show us what the best option is, not just a better one. In this scenario, let’s look at the exact same data, but in the larger context of the test that was really run:

In this case, we still have the same 2.38% lift, but we can see that in a larger context, that is only the 3rd best option out of the 7 different ones we are looking at. Had we failed to set-up the campaign to look for the larger context, the new would have thought we were accomplishing something, while in reality we would have been throwing away 14% lift (16.44% – 2.38%). Would your pat yourself on the back if you were reporting a 14% net loss to the business? Do we reward you for the 2% gain or the 14% loss? This is a real world situation, but this plays out all the time when you fail to look past opinions and you only test what someone is asking for or wants to see win. We fail to get perspective, so we are leaving winners our there left and right, winners that would dramatically impact the entire business. Why then is it ok to validate some basic “hypothesis” without diving into the larger context and looking for the best answer?

Not only are you actually losing money left and right when you do this, but you are also driving your optimization in the future to suboptimal paths. This is how you get into local maximums and how programs can get stale. This is also why test ideas are the least important part of a test program, since they only constrain people’s imagination and their ability to look at feasible alternatives. Testing and optimization should free people up to go far past their comfort zones, as the system only really works when you get great divergent inputs. The more divergent, the better the inputs, the more likely it is that you will get a far better outcome for your business.

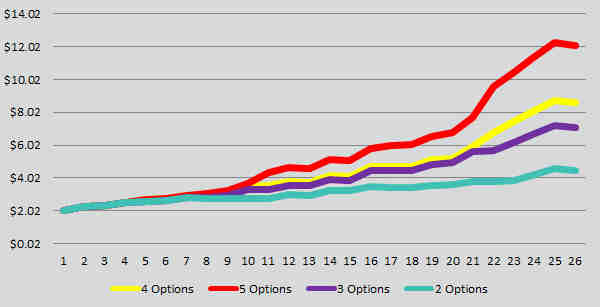

Overtime, this can have massive impact to the bottom line of any business. Here is a breakdown of a random number generator using normal distribution and the power of options (you only choose the best performer) looking at the impact of having 2, 3, 4, and 5 recipes in all your tests:

There is little to gain from running more tests, it is far important to run better tests and to look at alternatives, not to sit in a validation world of making people happy. If you fail to tackle the test with discipline and by challenging people’s opinions, you are dramatically limiting any possible impact you get.

If nothing else, never take just the act of getting a winner as a measure of a successful test. That is a sign that you are not trying to improve the business, just make yourself look good. Instead look at optimization as the ability to measure feasible alternatives, to have an active data acquisition which allows you to measure paths and to go down the best path. Do that, and you will add magnitudes greater value to all the actions you take.